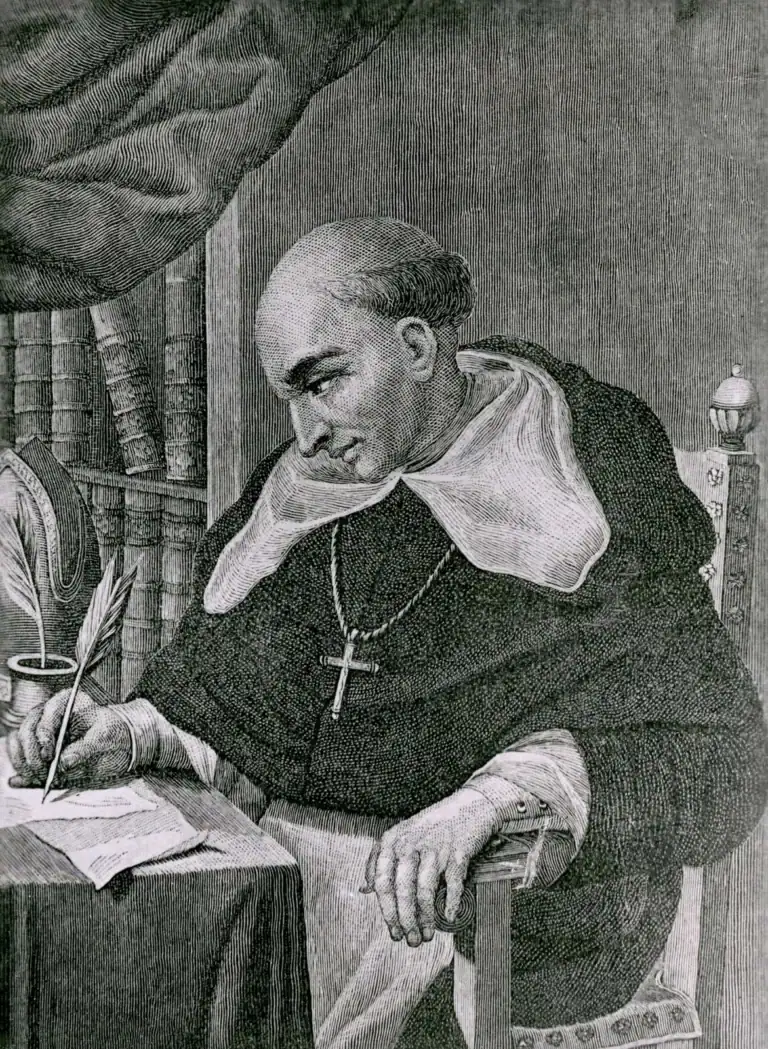

From Conquistador to Champion: A Strange Conversion

Bartolomé de las Casas (1484–1566) was born in Seville into a family that had mercantile and colonial interests. Early in life he traveled to the Caribbean and received land and Indigenous labor under the encomienda system. Over time, however, he became acutely aware of the suffering and injustice that system inflicted on the native peoples.

His transformation is one of the more dramatic in Christian history: he renounced his privilege, freed his Indigenous slaves, entered the Dominican order, and dedicated his life to pleading before Spanish courts, the papacy, and the crown for the rights and dignity of Indigenous communities.

In the Midst of Empire: Witnessing Horrors

Las Casas lived at the intersection of empire, colonial conquest, and the Christian mission. He didn’t merely debate in sterile halls — he had seen the devastation firsthand: forced labor, violence, exploitation, and mass death.

His most famous work, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (original Spanish Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, written 1542, published in 1552), is a searing, eyewitness indictment of colonists’ cruelty. You can read the full text (in English translation) via Project Gutenberg: A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Project Gutenberg

Other editions and excerpts are available via archives and academic sites.

In that work, he describes how villages were burned, people forced into mines, children murdered, and societies decimated — not from disease alone, but from systemic, brutal policies of conquest.

Resistance by Word, Not Sword

Las Casas refused to resist with arms or violence. Instead, he resisted with truth, with theological moral force, with accounts that could not be ignored. He leveraged his position in the church and his access to royal courts to plead for reform and change.

He participated in the Valladolid debates (1550–1551), arguing against Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda’s view that Indigenous peoples were “natural slaves.” In those debates, he defended their fullness of humanity, their capacity for reason and faith.

He also composed “memorials” and legal petitions urging the crown to abolish or reform abusive systems like the encomienda and forced labor. One such document is his Memorial de remedios (also known as Parecer de fray Bartolomé de las Casas) addressed to Emperor Charles V. The Library of Congress

His resistance was costly. He faced pushback, ignored petitions, and entrenched colonial interests. Yet he persisted for decades.

Heirs of His Witness: What Resistance Teaches Us Today

1. Conversion of complicity matters

Las Casas’s life warns us that resistance often begins with naming one’s own complicity. He was not an outsider railing from afar; he was deeply tied to the system he later opposed.

2. The power of testimony

Truth-telling is one of the most radical acts in a culture of denial. His detailed, agonizing descriptions challenged the complacency of Europe and began shifting legal and moral frameworks.

3. Faith-bound courage

His resistance was rooted in his Christian identity — not in nationalism or political ideology. He refused to let Christian faith be co-opted by empire’s violence.

4. Structural change is slow and imperfect

Though he helped spur reforms (e.g. the Spanish crown’s New Laws of 1542, which attempted to limit abuses) his victory was limited. Real change in law and practice lagged. But his persistence helped reframe moral horizons.

5. Solidarity across difference

He insisted Indigenous peoples were not enemies, but neighbors in need of justice. His resistance invites us to see those oppressed not as abstractions, but as human persons created in God’s image.

Questions for Reflection & Application

In what ways am I benefiting from unjust systems (social, economic, cultural)?

What voices of suffering am I refusing to hear?

How can I witness truth—through stories, actions, advocacy—in my own context?

What reforms or institutions need moral pressure today (immigration, incarceration, racial justice, land rights)?